From Dushanbe there is only one way east: the Pamir Highway with its different branches through various valleys. Different from what its name suggests, the Pamir Highway isn’t actually a highway. Especially the valley we chose has more stones and sand than asphalt. Read on, if you’d like to know what 250 kilometres of worst gravel road do to wo/man and machine.

The road we chose leaves Dushanbe to the south across two mountain passes at around 2,000m altitude and then drops into the deep valley of the Panj river along the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. On our way down we teamed up with a few other cyclists from Switzerland and France and, for a few days, often met them in the evenings to camp together.

The beginning of the valley is pure cycling joy. Here the road consists of mostly excellent tarmac and leads through a gorgeous landscape along rough mountains. On the opposite side of the river, small Afghan villages of little clay houses press against steep slopes so close by the river that sometimes they appear to risk falling into it.

Our goal was to reach the small but lively mountain town of Khorugh which seems to be perfectly prepared for overland travellers like us with dozens of hostels and homestays and even an Indian restaurant in town.We didn’t stay long though, as we were looking forward to our next stretch of road: the infamous Wakhan valley.

The Wakhan valley

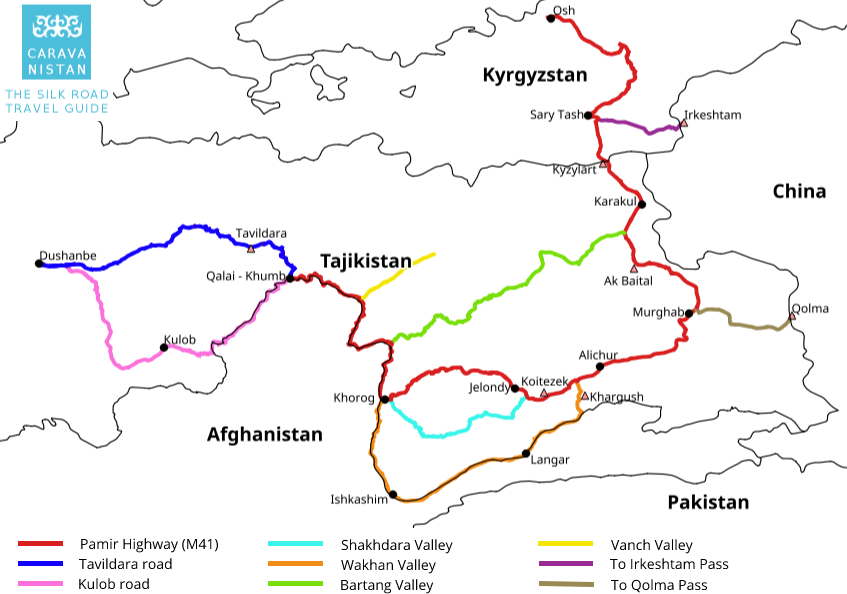

The main Highway leaves Khorugh to the east (the red road on the map). It was built in the 1940s by the Soviets and has thus little history. The Wakhan, in contrast, (beige road) has been inhabited for over two thousand years and features ancient petroglyphs, natural hot springs and a string of tiny, green villages as it continues south along the border with Afghanistan. We were excited!

The Wakhan is about 320 kilometres long and two thirds of it gently climb from 2,000m to an elevation of 3,000m, while the rest is steeper and crosses the Khargush pass at 4,200m before dropping back down to the Pamir high plateau and main road (red) at 3,800m. The valley is, however, also known to have some very bad roads built with large, lose gravel and deep sand and to be a big challenge for cyclists and motorists alike.

But hey, after the nightmare we rode on in the Uzbek desert, how bad can a road be? Nothing can shock us anymore, right? Wrong! After some 50 km of nice surface between Khorugh and Ishkashim, we were right back into the mess.

But besides the bad road, the Wakhan holds another interesting challenge for cyclists: Despite the first half being relatively densely populated, the availability of goods, fresh food items in particular, is very limited. After Khorugh, villages feature only teeny tiny grocery stores. No tomatoes, cucumbers or other veggies, no bread, no eggs. Even potatoes are hard to find.

Usually those shops would offer only the most basic goods people cannot grow on their own: shampoo, toothpaste, oil, pasta, sometimes rice, lots of sweets and biscuits. We were making jumps of joy when we found some weird sausage or a pack of expired mayonnaise that had never seen a fridge in its life. For cyclists this means carrying a lot of extra food.

Camping with soldiers

The border as well as the denser population in the Wakhan also had downsides for us. We had read in cycling forums that wild camping along the Afghan border sometimes causes problems. As any sensitive international border, the Wakhan is teeming with border guards and army posts. So, if you want to sleep here, the trick is not to be seen. At least once we failed.

It could have been such a relaxed evening. Two Swiss cyclists, Céline and Chantal, Frances and I had been exhausted from a long day of cycling and found a cute little spot maybe 20 metres below the road right by the banks of the Panj. Here, the river is wide and wild and would be very hard to cross. When dusk came, we pitched our tents, aware that they would be visible from the road. Some boys from a nearby village were playing a few hundred metres further and watched us with curiosity, nothing unusual really. We prepared diner.

Just as the pasta started cooking, a group of five Kalashnikov-laden Tajik soldiers appeared. Their leader wanted to see our four passports and checked very thoroughly every page of them as well as our visas and the so-called GBAO permits needed to travel the Pamirs. It took ages until he eventually told us: you cannot stay here. Too dangerous. Border. Taliban. Terrorists. Negotiations season was on!

Using Frances’ offline translation app, I started unpacking the arguments I had prepared in my mind. First mildly: we are very tired (true), have cycled a lot today (false), have already cooked diner (true), and cannot pack up our stuff now (false). The lead soldier listened carefully and took a looong time to reply, staring into the distance after every few words he typed into Frances’ phone — as if he was contemplating what to do with us. I tried to explain that we are aware of the risks but had camped several times on this border without problems. I showed him our previous camp spots on the map. He glanced into the distance. “Different”, he said, “Other parts of the valley no problem but here, Taliban only 40 kilometres away.”

After some 30 minutes of back and forth he suddenly seemed to have changed his mind: he had to ask his superior for permission. He and his men would be back in half an hour to let us know the decision. This could mean two things, I thought.

- Either he’s tired of debating with me and needs a face-saving way out. In this case we wouldn’t see the soldiers again. Excellent.

- Or he’s really going to talk to his superior, be back, and in case of a No will have no authority anymore to let us stay without disobeying his boss. Less excellent.

I went back to the camp and ate my now cold pasta. I had hope. We chatted a bit, washed our dishes and — as nightfall had come — disappeared in our tents. It was maybe 9pm when the soldiers were back. The boss had said “No” and I started to worry as I was convinced that, no matter how friendly our soldiers, there was no way out. I nevertheless pulled out my last argument: I understand their concerns for our safety but, given that it’s already dark, cycling on the narrow, unlit mountain road was much more dangerous for us. So much traffic, too risky. “We leave at first sunlight in the morning, okay?”

The leader looked at me as if he was pondering over my proposal. Again staring into the distance. Then, slowly, typed into the phone: It is his duty to protect us at the border. If we want to sleep here, he cannot do that. We stay at our own risk and responsibility. I agreed, thanked him, and the group along with their Kalashnikovs disappeared into the night. We never saw any terrorists but had an excellent, quiet night. The next morning we were on our way further into the Wakhan valley.

Almost the end

Somewhere in the middle of the valley, my carrier fell apart. Now, it had four broken points, including the one the welder in Dushanbe had fixed two week earlier, and wouldn’t likely hold my panniers anymore I presented the others with what I thought were the options:

- Continue in the hope that the carrier will hold up (unlikely);

- Find someone in the Wakhan who can weld aluminium (very unlikely);

- Try getting a lift and end my trip there and then (possible).

I honestly thought that was it. But I had made up my options without the Wakhan villagers. Once we stopped we were surrounded by a group of curious guys. I showed them my carrier, kaputt kaputt, and they led me and my bike along small sandy paths into the village and to the local mechanic. Standing next to an old Lada on repair (“Rrrrussian quality, verrrry goood!”) he pulled out his welding machine and gave it a try. As expected, the machine was only capable to welding steel, not aluminium. The result was immediately pulverised under pressure.

I was now certain this was the end (of my trip), when another guy came up with a steel wire so thick that it could hardly be bent with bare hands. Using heavy pliers they wrapped it around the different carrier poles on both sides, wired it once around the carrier and knotted the ends together. Before I could drop my jaw they had stabilised the whole thing, looked happy, handed me a huge loaf of bread and refused any payment for it. Those guys have saved my journey and I’m not sure they even realised how valuable their selfless help was to me.

The end of the wakhan

We pushed deeper into the Wakhan valley, across sometimes fist-deep gravel and sand, slowly climbing towards the mark of 3,000m. At the small village of Langar, Frances and I took a rest day. We hadn’t had a break since Khorugh and we knew that Langar was the last settlement before the road turned north across the Khargush pass at over 4,300m which would lead us out of the Wakhan and back to the Pamir Highway’s main road.

We chose a small homestay for the night (in fact, Langar is so popular as a last stop among overlanders that people jump at you on the streets in the hope that you’d stay at their place), politely knocked down the price a bit and settled in for a rest: take a shower, wash some clothes, stock up our food reserves for the days ahead, and — do some sightseeing!

Turns out that Langar is host to some Bronze Age open air petroglyphs up in the mountains which are are hard to find but fascinating to see. After half an hour scrambling uphill on a steep footpath in the midday heat, we crossed a little river and found ourselves standing on a naked rock face covered in carved images of animals and unknown symbols.

Unfortunately, with no protection the old petroglyphs are quite weathered. Moreover, villagers have added tons of new carvings, from perfect copies of the old ones to random Cyrillic writings, hearts and other modern symbols. For non-experts like ourselves it has thus become quite hard to distinguish old petroglyphs and recent vandalism. I have still added the footpath to Open Street Maps, just in case future visitors have similar difficulties finding the place.

Into the high mountains

On 23 June we left Langar and headed into the wild upper Wakhan. Between here and the tiny town of Alichur on the high plateau of the Pamirs, there is no other human settlement except a border control point and some shepherds. The area also becomes noticeably drier, so we filled up our water bags and started the ascent.

Just out of Langar, an extraordinarily bad gravel road climbs uphill in six steep curves and continues to haunt us with deep sand and lose stones for another 20 or so kilometres. I started cursing at the valley. This is not the kind of riding I usually enjoy. And yet, over and over I ended up stopping, taking a deep breath and being speechless in front of the beauty of the mountains surrounding us.

Langar to Alichur, that’s only 120km. Usually a distance which, despite the elevation, we would casually ride in two days. In the Wakhan it took us three, that’s how much the road slowed us down. At times, we would not even do 40km per day but were rewarded with wonderful camping spots, only a handful of cars per day, and the crossing of the Khargush pass at 4,344m with stunning views onto the snow-covered summits around us.

Alichur, which I hoped would be a bit bigger, is the embodiment of a wild east town. Small houses bent by the wind, randomly spread across a mountain plateau so huge that the town appears even smaller than it is. Like in the Wakhan, no internet, limited electricity, no running water. A mosque, a few tiny shops, no agriculture, no industry. It seems that people in Alichur live of cattle and tourism and life is sustained by what Tajik trucks deliver via the Pamir Highway.

From Alichur, it is only a bit over 100 kilometres until Murghab, the largest town in the Pamirs, so we only stay one night and cycle on. After a little uphill the road to Murghab is mostly descent on excellent tarmac surrounded by beautiful mountain scenery. We loved the ride and because we had tail wind it was easy. We reached Murghab in the evening and settled down for a rest day in order to do some planning for what lied ahead.

Where the fellowship ends

The small Soviet mountain town of Murghab with its 7,000 residents is a fascinating place. There is running water but electricity comes from petrol-based generators and only in the evenings. There is mobile internet but it’s so slow that sending a Signal message can take more than 10 minutes and booking a flight several hours.

The local bazaar (run out of old shipping containers) is surprisingly well equipped for such an isolated place: there are tomatoes, bicycle parts, cucumbers, and factor 50 sunscreen. Our hostel had hot showers and good food for dinner and that’s all Frances and I needed for our last day together. Because Murghab was also the place where we had planned to split up.

Frances wants to continue following the Pamir Highway all the way to Osh in Kyrgyzstan and then climb lots of more mountains before reaching the capital Bishkek, where she can get her visa for Mongolia. I plan to head east across the newly opened Qolma pass (4,366m) into the People’s Republic of China.

Stay tuned for my next post about this last strip of my journey from Belgium to China! 🚴💨

Just finish this journey without any harm. Your journey seems to get harder day by day. Considering you are on your own now, i wish you a better luck than what i wished before. Keep posting 🙂